History (1992): Intel Cutting Down Flash Card Prices

4, 10 or 20MB at $163.50, $331.50 and $611.50 respectively for OEM orders of 10,000

By Jean Jacques Maleval | June 12, 2020 at 2:10 pmIntel Corp. (Santa Clara, CA) has made huge efforts to reduce the prices of its new flash cards and increase their capacity that now reaches 20MB.

Small microcomputers will take advantage of them, but it will take more time before they can compete with most HDDs.

Intel is laying out its new cards, the Series 2. They are made from a new 1MB (16x64KB) flash cell, or 28F008SA, that costs $20.90 in OEM quantity 10,000, and have an 85ns access time, they can each support 100,000 write cycles.

These non-volatile and erasable memories, mounted on a card, the size of a credit card, have a capacity of 4, 10 or 20MB depending on the models. The iMC004FLSA, iMC010FLSA and iMC020FLSA cost $163.50, $331.50 and $611.50 respectively for OEM orders of 10,000.

They will be available this month and manufactured by NMB Semiconductor, a subcontractor of Intel.

The decrease in prices is amazing when you remember that, just a few weeks ago, SunDisk Corp. (Santa Clara, CA) offered evaluation units of its own 40.9MB flash card for $8,000.

A few days ago, Advanced Micro Devices (Sunnyvale, CA), Intel’s largest competitor, was launching a 2Mb flash type component, to be mounted on cards, and only requiring a 5V supply (compared with 12V for Intel) and with a record access time of 45ns (compared with 85).

These innovations won’t be the last ones in this segment and are going to widen a market of $131 million last year, that should reach $1.55 billion in 1995 according to Dataquest.

In 1991, Intel owned 86% of it, compared with 7.1% held by AMD, 1.7% by Toshiba, etc.

Several manufacturers who produce microcomputers smaller than notebooks have already adopted this type support that’s takes up less space in their devices than diskette drives and especially HDDs. And these cards, that can fit in a pocket, can easily be placed in a machine, just like cards into video games, on account of a standard 68-pin PCMCIA connector.

Additionally, they hardly use no electricity, have a remarkable reliability and shock resistance, and an unequaled data access or transfer rate.

But there are still two problems before this new type of media becomes widely used, its price and a sluggish writing time.

Even if prices lower, an end user will have to pay more than twice the OEM price given above just for an Intel’s external memory with today’s highest capacity, 20MB. But this capacity is no longer enough for actual programs and applications. The proof is that 20MB drives hardly sell anymore. The cost of 1MB on a magnetic support is much below Intel’s prices.

Additionally, it’s hard to imagine cards, even with smaller capacities, replacing diskettes to distribute or exchange software or data.

Another disadvantage, which isn’t frequently put forward, is, that, if reading a flash card is almost instantaneous, 200ns, updating is a big problem. First you have to erase a block, 64KB at a time, before you can write new data, and here it’s closer to a second (!) to erase, without the writing time, which takes about 10ms. A person in charge at Intel admitted that to format a flash card, which means completely erasing it and writing over on it, took as long as with a diskette.

To avoid this type of problem, the Flash File System, developed by Microsoft for its special memories, always reserves erased blocks, to be written on, which means that the useful capacity of the card is slightly lower. But, if the size of this block is not big enough for a given backup, it will then mean a long write cycle.

To demonstrate its new flash cards at a press conference in Paris, Intel used 3 different brand of notebooks (Acer V386SL, Sharp i386SL and Hyundai Neuron 386SU25), all equipped with its card, but also with a 60 or 80MB HDD and a 3.5-inch FDD. On this kind of unit, a flash card is perfect to run a new Bios or an OS, or to boot the computer as it’s turned on, with an unequaled read cycle time. Otherwise, rotative magnetic memories, especially Winchester drives with prices shrinking as fast as sizes, are going to keep on.

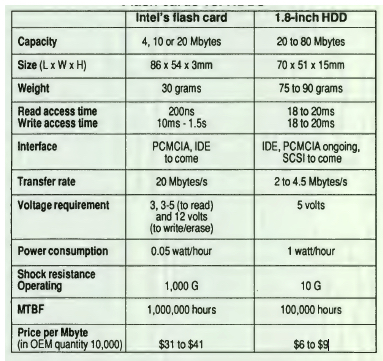

If Conner Peripherals (San Jose, CA), the number two in independent disk drive manufacturing, signed an agreement with Intel to develop an IDE interface for flash cards and to distribute them, it’s not just to compete with itself. The only possible competition, between 1.8-inch drives and flash cards (see chart) is in the thinnest microcomputer segment. This is for now, because it’s obvious that all the advantages of a semiconductor memory will be undeniable compared to another one using a heavy electromechanical system.

Flash cards vs. HDDs

This article is an abstract of news published on the former paper version of Computer Data Storage Newsletter on issue ≠52, published on May 1992.

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter