History 2002: IBM Driving Diskless

Transferring HDD activity to 70%-30% joint venture led by Hitachi

By Jean Jacques Maleval | June 7, 2023 at 2:00 pmBig Blue, the first company ever to manufacture a HDD, is now the latest to exit the industry, after transferring the activity to a 70%-30% joint venture led by Hitachi.

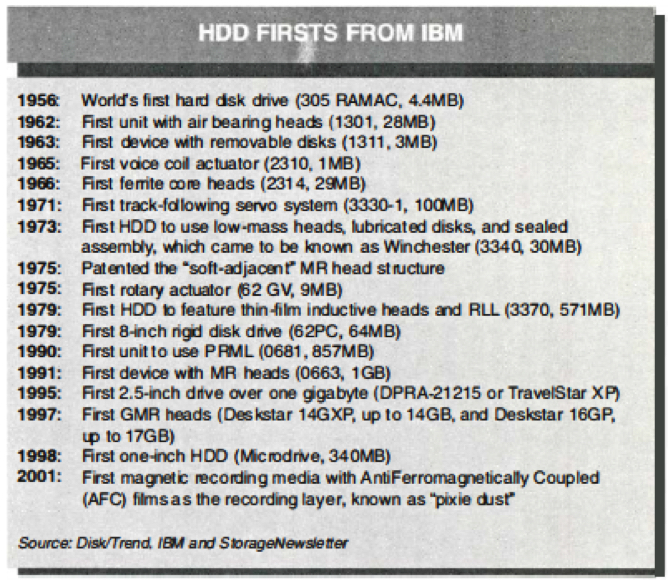

There can be no doubt about the historic implications for the WW storage industry. IBM, first to come up with the idea of a HDD in 1956, and the undisputed technological leader, inventing nearly everything important in the domain, is throwing in the towel 46 years later, after concluding it simply cannot turn a profit in this market.

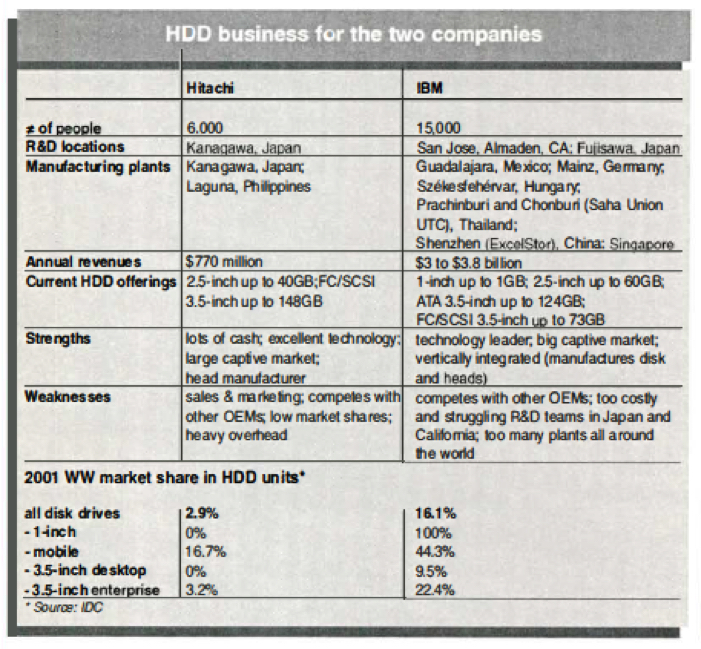

Initial rumors of an acquisition by Hitachi have since been confirmed. What we know from the April 17 announcement: Hitachi and IBM have combined their HDD operations into a new joint venture based in San Jose, CA, 70% owned by Hitachi, 30% by IBM, integrating R&D, manufacturing, sales and marketing operations and combining IP. Hitachi will make a payment (of an undisclosed amount) to IBM for the HDD assets. Both companies will source a major portion of their HDDs from the new venture.

What we still don’t know:

The name of the joint venture (which we will refer to here as “HIBM”) or its chief executive, the restructuring plan, or the new joint line of HDD drives.

We did get one further bit of info, however: “The recent IBM alliance announcement involves the disk business only. Nothing has changed regarding our IBM LTO business,” explained Glen Allen, manager, IBM’s OEM tape storage marketing, LTO business line management.

Getting out of a profitless division

Big Blue has decided to put an end to a declining HDD business that was losing money. For its most recent quarter, ended March 3, revenue and OEM sales for HDDs dropped by 29% from one year to the next, mostly due to difficulties with enterprise drives. The overall HDD activity posted a $137 million loss for the last 3 months of 2002, with gross margin’s down 16 points Y/Y. Ever since the beginning of 2001, we’ve noted a certain listlessness in IBM’s HDD activities.

As a result of technical difficulties, the company lost nearly 3% of its market share and a significant number of customers in the enterprise segment, falling into third position behind Seagate and Fujitsu since 4001.

Worse yet, the firm experienced a worrying technological stall. In the past, Big Blue made it a point to demonstrate with regularity that it was the world leader in areal density. This has not been the case lately.

The company is nowhere near Read-Rite, which has perfected an advanced GMR head to demo 130Gb per square inch areal density with a disk from MMC Technology and read channel from Marvell.

Even Hitachi seems to be outpacing its partner, working on a perpendicular magnetic recording at 107Gb per square inch, with samples expected in 2004.

With the same kind of technology, named “Current-Perpendicular-to-Plane” mode GMR head, Fujitsu hopes to achieve 300Gb per square inch!

IBM offers no FC/SCSI units over 73GB.

As for desktop units, while the firm was the first to hit 20GB per platter in 2000, it will be one of the last at 40GB per disk.

For 2.5-inch devices, its main rival, Toshiba, was always a length behind. Not anymore. IBM unveiled its 20GB per disk unit well after Toshiba announced 30GB per platter, and there’s still no word from IBM on that capacity point.

Since mid-2000, its 1-inch Microdrive has been stuck at 1GB, thus losing the capacity advantage it once held over flash cards.

Are the motives behind this disengagement truly financial? It’s conceivable that IBM simply no longer believes in the future of HDDs, sensing the approach of the superparamagnetic limit, and therefore has decided that it would be preferable to focus on other technologies.

And yet, it’s highly unlikely that any optical or silicon technology could seriously displace the HDD in the foreseeable future.

Inconsistent management

As far as management was concerned, confusion has reigned. There had been a state of virtual competition between research centers in Fujisawa, Japan, and San Jose, CA. After first transferring responsibility for 3.5-inch drives to the Japanese subsidiary in recognition of its success with 2.5-inch units, Big Blue subsequently handed power back to its California site for enterprise units. Keeping up with the whereabouts of the disk drive business became a full-time job, requiring daily monitoring of the company’s reorganizations. When last we heard, it legally belonged to the Technology Group, headed by SVP Jim Kelly, but in fact fell under the responsibility of Storage Products Division (SPD) headed by Walter Raizner, who in turn, if we understand correctly, since even within IBM it’s not quite clear, reports to Lynda Sanford, SVP of the storage division, who always has much to say on the topic of storage subsystems and software but who has scarcely uttered a word on the HDD component of her activity…

Would it not have been wiser a long time ago to have created a separate business unit, if not an entire subsidiary, for HDDs and their components, thus providing a greater degree of autonomy, with its own profit center, in order to place the business on an equal footing with rival independent manufacturer? This could have led to a more aggressive commercial strategy, not to mention a more rational approach both to R&D, notoriously too costly, by combining teams from its Californian and Japanese research facilities, and to manufacturing, with plants currently scattered throughout the world.

Even if this business unit also proved unprofitable in the long run, it would have constituted a well-defined and distinct unit, far more attractive for potential buyers or mergers.

IP never fully realized

Why also has IBM, with thousands of storage patents, failed to make the most of its technological know how, instead allowing the competition to plunder most of its ideas without reacting? We’re not defending the optical disk model, where a handful of firms have been getting fat on royalties since the inception of the CD-ROM, a mentality that entirely drives that business.

But Big Blue might at least have protected a bare minimum of its IP. Unfortunately, the company is a victim of its own history, that of a computer giant living in justifiable fear of an attack from the US Justice Department and the threat of antitrust action.

As a result, the company allowed a significant IBM compatible market to grow and thrive, both at the level of mainframes and peripherals, particularly tape and magnetic disk.

This may not have seemed so terrible when IBM commanded a majority of the market share, but since the arrival of HDDs for PCs, independent manufacturers, Seagate first among them, have gradually edged IBM out to the point where today it holds only a minority position, despite its fundamental technological innovations (see inset below, “HDD firsts from IBM”).

When we think that tiny Rodime managed to squeeze virtually all HDD makers, 18 in all, excluding Quantum, for who knows how much money in all – Seagate paid $45 million in 2000, and even IBM forked over some $30 million in 1990 – just for its patents on DSPs and the 3.5-inch form factor, it doesn’t seem unreasonable that the firm that did so much to advance the state of HDDs get some tiny return on its contribution, if only $1 per drive, roughly 1% of the average unit cost, which would nevertheless have meant $200 million in 2001 alone, all of it pure profit for IBM.

History might then have played out differently.

Diplomatic merger

IBM’s new CEO, Sam Palmisano, then, has made the move his predecessor, Lou Gerstner, who always had a tenderness for the disk drive business, was reluctant to make. Of course, Big Blue can’t just dump a part of its company that accounts for nearly 15,000 employees. How do you sell it off, anyway? Who could afford a money-losing monster like that? Even the 2 HDD leaders, Seagate and Maxtor, would sink under such a weight.

No, IBM had to find a diplomatic way out, one that would reassure shareholders, customers and employees alike. For this reason, the idea of a joint venture with the giant Hitachi group ($66 billion in sales, 341,000 people) makes perfect sense. As far as we can tell, however, this joint venture, under Hitachi’s 70% control, corresponds for all intents and purposes to a virtual withdrawal from the HOD industry by IBM, since it’s more or less a hand off to its Japanese rival.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Hitachi will pay over $1 billion to IBM in the transaction. It’s a laughable amount, when you consider all of Big Blue’s assets in the sector: patents, a team of the highest-level engineers, giant plants on 3 continents.

What HIBM will look like?

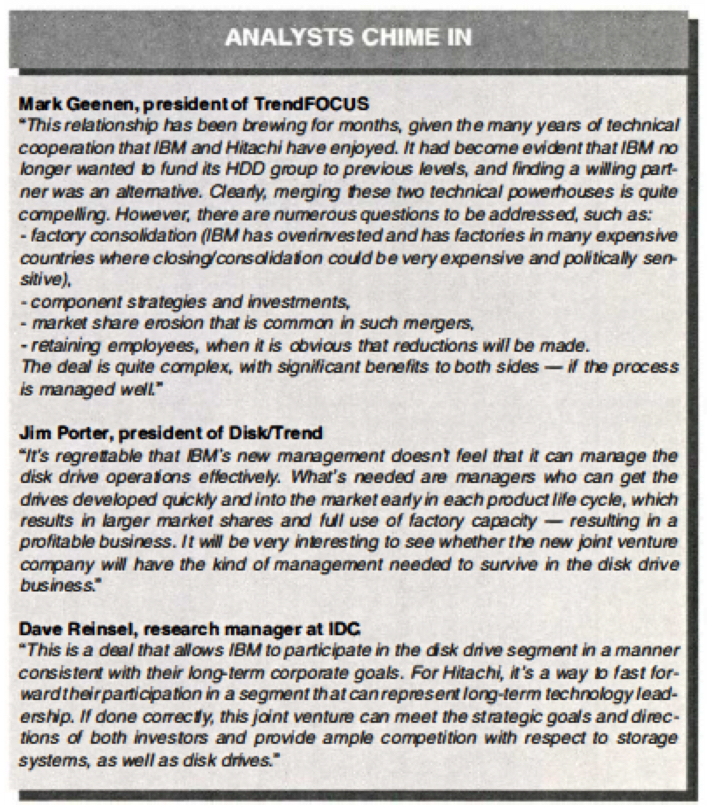

Almost always, the size of a merger is not the sum total of the two businesses to be joined; this sort of union is often difficult, particularly in the HDD industry.

Recall the problems Seagate experienced when it began absorbing Conner Peripherals in 1996, and to a lesser extent, Maxtor with its acquisition of Quantum HDD in 2000.

For HIBM, this could prove even tricker, even if the corporate culture of the 2 new partners is similar: both, after all, are major multinationals involved in mainframe disk and tape drives, and are also important players in SAN for mainframes and open systems (Hitachi via HDS in the US).

What’s more, Hitachi’s technological know-how is also of high quality. Yet the Japanese conglomerate is an enormous machine that moves slowly and proceeds with great caution. Nor will it be simple to restructure to such widely-flung organizations. HIBM’s HQ will be in San Jose, but the Japanese will make the decisions … about what, though?

What restructuring?

HIBM cannot possibly maintain 4 R&D centers: IBM’s in San Jose, Almaden and Fujisawa, plus Hitachi’s in Japan.

The first victims of the consolidation will no doubt be IBM’s plants in Mainz, Germany and Szekesfehervar, Hungary, since it seems more likely that the company will prefer the German facility, its own enormous HICAP (Hitachi Computer products Asia corp. Philippines) factory, which dates from 1995 and employs 4,500 people who assemble 3.5-inch and 2.5-inch HDDs, as well as manufacturing magnetic heads.

As a result, the last plant to produce HHDs in Europe, IBM’s plant in Hungary (managed from Mainz), which assembles 2.5-inch and desktop HDDs, also faces an uncertain future. In Germany, employing some 2,000 people, the old 160,000 square meter facility (founded in 1965), including 45,000 square meters of clean rooms, currently boasts production capacity of 40 million rigid disks, 8,000 wafers and 100 million sliders per year.

The factory has been kept alive through the efforts of its GM, Walter Meizer and his team, who prolonged its life by transferring drive assembly to Hungary. If the 2 were closed, there would no longer be any HDD drive plants in Europe (apart from Seagate’s facility in Ireland, which makes components). It will be difficult for HIBM to ignore IBM’s largest factory in Singapore (4, 500 people), but the new alliance is likely to take up the question of whether to keep Big Blue’s site in Mexico, which makes Winchester heads, disks as well as tape heads. It’s hard to say what will become of the two outfits in Thailand (for desktop and Microdrive HDDs), one in partnership with Saha Union, or of the recent subcontract manufacturing agreement with ExcelStor (desktop units) in China, not to mention the Chinese joint-ventures with Kaifa for HDD substrates and HGAs.

What is certain is that there will be major trimming among HIBM’s 21,000 total employees, from the upper echelons on down. Another likely difficulty for HIBM will be to harmonize 2 product lines that are not intuitively complementary. Hitachi is only in 2.5-inch HDDs and enterprise drives. IBM offers both, as well as 7,200rpm desktop units and a small number of Microdrives. How well HIBM performs, ultimately, depends on how quickly, and how optimally, Hitachi’s regrouping proceeds. But it won’t be easy.

One less HOD manufacturer, and what that means

As long as there are at least 2 HOD manufacturers, prices will continue to fall. Neither the disappearance of Conner nor of Quantum HOD changed this tendency in the past.

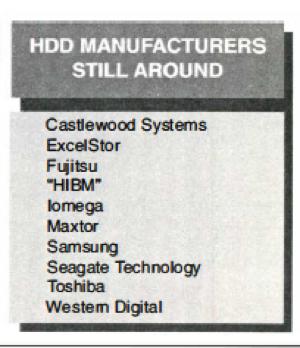

With the HIBM alliance, only 10 disk makers remain in the world (see inset, below), including seven majors: HIBM, Fujitsu, Maxtor, Samsung, Seagate, Toshiba and WD.

By combining the sales volume for both Hitachi and IBM, we get a WW market share of roughly 19%, which places HIBM in 3rd place after Seagate and Maxtor, ahead of WD.

This doesn’t really alter the rankings, of course, since IBM already held third place.

However, in terms of revenues, HIBM, which comes in at around a total of $4 billion, may just displace ≠2 Maxtor, with $3.8 billion, assuming that the full combined sales of the 2 companies are realized, something that is unlikely in the short term.

In fact, it will take at least a year, perhaps more, to reorganize the 2 entities.

As always, during that time, the competition will not be standing still.

“This alliance is good news,” affirmed Didier Tressaert, Maxtor’s European VP. “I’d rather compete with someone from Hitachi than someone from IBM.”

Nor would it be surprising if a 3rd player decided a bit sooner than planned to enter the 2.5-inch HDD race in order to take advantage of the HIBM transition, and thus not allow only Toshiba to profit. Seagate is the most likely, but perhaps Fujitsu could also prove to be one of the first big winners in the enterprise drive segment, where IBM has traditionally been the grand rival.

Note: Finally, Hitachi acquired IBM HDD business for $2.08 billion in May 2022 and then was bought by Western Digital for $4.8 billion in 2011.

This article is an abstract of news published on issue 172 on May 2002 from the former paper version of Computer Data Storage Newsletter.

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter