From The University of Tokyo, High-Capacity Tape for Big Data

New magnetic material and recording process can vastly increase data capacity.

This is a Press Release edited by StorageNewsletter.com on October 16, 2020 at 2:15 pmFrom The University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Science / Faculty of Science

Although out of sight to the majority of end users, data centers work behind the scenes to run the Internet, businesses, research institutions and more.

These data centers depend on high-capacity digital storage, the demand for which continues to accelerate. Researchers created a new storage medium and processes to access it that could prove game changing in this sector. Their material, called epsilon iron oxide, is also robust so can be used in applications where long-term storage, such as archiving, is necessary.

It may seem odd to some that in the year 2020, magnetic tape is being discussed as a storage medium for digital data. After all, it has not been common in home computing since the 1980s. Surely the only relevant mediums today are SSDs and Blu-ray discs. However, in data centers everywhere, at universities, banks, internet service providers or government offices, you will find that tapes are not only common, but essential.

Though they are slower to access than other storage devices, such as HDDs and solid state memory, tapes have high storage densities. More information can be kept on a tape than other devices of similar sizes, and they can also be more cost effective too. So for data-intensive applications such as archives, backups and anything covered by the broad term big data, they are important. And as demand for these applications increases, so does the demand for high-capacity tapes.

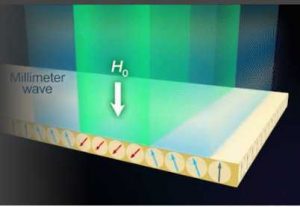

Magnetic pole flip. Millimeter waves irradiate epsilon iron oxide,

reversing its magnetic states representing binary states ‘1’ or ‘0’.

(© 2020 Ohkoshi et al.)

Professor Shin-ichi Ohkoshi, Department of Chemistry, University of Tokyo, and his team have developed a magnetic material which, together with a special process to access it, can offer greater storage densities. The robust nature of the material means that the data would last for longer than with other mediums, and the novel process operates at low power. As an added bonus, this system would also be cheap to run.

“Our new magnetic material is called epsilon iron oxide, it is particularly suitable for long-term digital storage,” said Ohkoshi. “When data is written to it, the magnetic states that represent bits become resistant to external stray magnetic fields that might otherwise interfere with the data. We say it has a strong magnetic anisotropy. Of course, this feature also means that it is harder to write the data in the first place; however, we have a novel approach to that part of the process too.”

The recording process relies on high-frequency millimeter waves in the region of 30-300 gigahertz, or billions of cycles per second. These high frequency waves are directed at strips of epsilon iron oxide, which is an excellent absorber of such waves. When an external magnetic field is applied, the epsilon iron oxide allows its magnetic direction, which represents either a binary ‘1’ or ‘0’, to flip in the presence of the high-frequency waves. Once the tape has passed by the recording head where this takes place, the data is then locked into the tape until it is overwritten.

Data center. Digital tapes are common in data centers.

(CC-3.0 Wikimedia Commons/Hannes Grobe )

“This is how we overcome what is called in the data science field ‘the magnetic recording trilemma,’” said Marie Yoshikiyo, project assistant professor, Ohkoshi’s laboratory. “The trilemma describes how, to increase storage density, you need smaller magnetic particles, but the smaller particles come with greater instability and the data can easily be lost. So we had to use more stable magnetic materials and produce an entirely new way to write to them. What surprised me was that this process could also be power efficient too.”

Epsilon iron oxide may also find uses beyond magnetic tape. The frequencies it absorbs well for recording purposes are also the frequencies that are intended for use in next-gen cellular communication technologies beyond 5G. So in the not too distant future when you are accessing a website on your 6G smartphone, both it and the data center behind the website may very well be making use of epsilon iron oxide.

“We knew early on that millimeter waves should theoretically be capable of flipping magnetic poles in epsilon iron oxide. But since it’s a newly observed phenomenon, we had to try various methods before finding one that worked,” said Ohkoshi. “Although the experiments were very difficult and challenging, the sight of the first successful signals was incredibly moving. I anticipate we will see magnetic tapes based on our new technology with 10 times the current capacities within five to 10 years.”

New magnetic recording method using millimeter/terahertz waves

Demonstration of focused millimeter wave-assisted magnetic recording, presenters:

-

Shin-ichi Ohkoshi (Professor, Department of Chemistry, School of Science, The University of Tokyo)

-

Makoto Nakajima (Associate Professor, Institute of Laser Engineering, Osaka University)

-

Masashi Shirata (Manager, Recording Media Research and Development Laboratories, Research and Development Management Headquarters, FujiFilm Corporation)

-

Hiroaki Doshita (General Manager, Recording Media Research & Development Laboratories, Research and Development Management Headquarters, FujiFilm Corporation)

-

Hiroko Tokoro (Professor, Department of Materials Science, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, University of Tsukuba)

-

Seiji Miyashita (Emeritus Professor, The University of Tokyo)

-

Takehiro Yamaoka (Chief Engineer, Analysis Systems Solution Development Dept., Metrology and Analysis Systems Product Div., Hitachi High-Tech Corporation)

Key points of work:

-

With increasing amounts of information, to achieve high-density recording in the future, researchers succeeded in proving the concept of “focused millimeter wave-assisted magnetic recording” as a new magnetic recording method that uses millimeter waves.

-

Focusing on epsilon iron oxide (ε-Fe2O3) and metal-substituted ε-Fe2O3, which are candidates for magnetic fillers of future magnetic recording tapes and also possess high-frequency millimeter-wave absorption properties for the beyond 5G era, they prepared magnetic films of ε-Fe2O3 and constructed a focused millimeter-wave generator using terahertz (THz) light source, and experimentally demonstrated “focused millimeter wave-assisted magnetic recording”.

-

The new recording method will enable the use of smaller magnetic nanoparticles for the magnetic recording media, and the recording capacity is expected to increase.

Overview of the work

A research group consisting of Professor Shin-ichi Ohkoshi of the School of Science, the University of Tokyo, Associate Professor Makoto Nakajima of Institute of Laser Engineering, Osaka University, and Manager Masashi Shirata and General Manager Hiroaki Doshita of Recording Media Research and Development Laboratories, FujiFilm Corporation, collaborated with Professor Hiroko Tokoro of University of Tsukuba, Emeritus Professor Seiji Miyashita of the University of Tokyo, and Takehiro Yamaoka of Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, to successfully develop a new magnetic recording method, ‘millimeter wave magnetic recording’, using millimeter and terahertz waves.

In the era of big data and the IoT, data archiving is a key technology. From this viewpoint, magnetic tapes [1] are actively used in cloud services and data archives for business purposes because they guarantee long-term data storage, low power consumption, and low cost. Consequently, the demand for magnetic tapes is growing. To archive an enormous amount of data, recording density needs to be increased. In this work, Professor Ohkoshi and colleagues proposed a new magnetic recording methodology, ‘Focused Millimeter wave–assisted Magnetic Recording, F-MIMR,’ to achieve millimeter-wave magnetic recording. To test this methodology, magnetic films were prepared using epsilon iron oxide [2], which is drawing attention as a magnetic filler for future magnetic tapes and also as a millimeter-wave absorber for beyond 5G [3] networks, and constructed a focused millimeter wave generator using terahertz (THz) light. Irradiating the focused millimeter wave to epsilon iron oxide switched its magnetic pole direction, and magnetic field writing was confirmed. F-MIMR is a magnetic recording method for the beyond 5G era, combining light/electromagnetic waves of beyond 5G networks and magnetic recording. Thus, F-MIMR could contribute to raising the magnetic recording density.

The results of this research published online in Advanced Materials on October 8, 2020, Japan time.

Details of the work

Millimeter wave technology is expected to play a significant role in the era of IoT. Millimeter waves (30–300 GHz) [4] have potential in broadcasting wireless communications, wireless data transmissions between cellular base stations, and traffic monitoring sensors in intersection areas for advanced driver assistance systems. For example, millimeter waves at an 80GHz frequency are widely used for car radars. Meanwhile, magnetic recording is drawing attention as a sustainable data storage system in the big data era. To further enhance the recording capacity to archive an exponentially increasing amount of data, the magnetic particle size must be reduced. However, as magnetic particles become smaller, the thermal stability of the magnetization decreases (the problem of superparamagnetism). In order to avoid the problem of superparamagnetism, enlargement of the magnetic anisotropy is necessary. Consequently, current magnetic recording heads cannot write against the strong magnetic anisotropy. This problem is called the ‘magnetic recording trilemma’ and is common for magnetic media, including HDDs and magnetic tapes. To resolve the trilemma problem, several types of recording methods have been proposed such as HAMR and microwave-assisted magnetic recording.

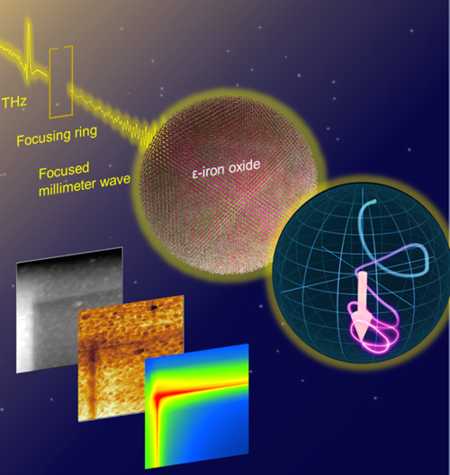

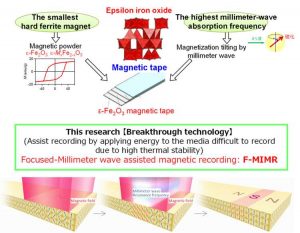

Ohkoshi and colleagues focused on epsilon iron oxide for two main reasons. First, it exhibits high-frequency millimeter wave absorption in a wide frequency range of 35 to 222GHz due to the zero-field ferromagnetic resonance and is expected to be used for beyond 5G applications. Second, it can also maintain spontaneous magnetization due to ferrimagnetism even with a single nanometer size particle. In this study, they prepared magnetic films based on metal-substituted epsilon iron oxide and propose a new recording methodology ‘Focused Millimeter Wave–Assisted Magnetic Recording (F-MIMR)’ based on a novel concept of “millimeter wave magnetic recording” (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Concept of ‘Focused millimeter wave-assisted magnetic recording’ (F-MIMR).

F-MIMR is a recording system using the characteristics of the world’s smallest hard ferrite, epsilon iron oxide, which exhibits high-frequency millimeter-wave absorption. The necessary magnetic field for magnetization reversal is reduced by the millimeter wave irradiation only during recording.

Click to enlarge

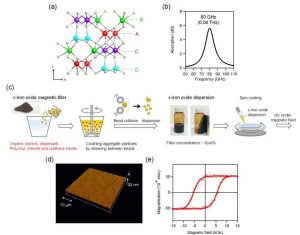

For the demonstration, magnetic films based on gallium-titanium-cobalt–substituted epsilon-iron oxide (GTC-type ε-iron oxide: ε-Ga0.23(TiCo)0.05Fe1.67O3) nanoparticles were prepared on a glass subustrate (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Physical properties of GTC-type ε-iron oxide(ε-Gax(TiCo)yFe2−x−2yO3)

and preparation of magnetic film.

(a) Crystal structure of GTC-type ε-iron oxide. Red, green, purple, light blue, and gray balls represent Fe atoms at A, B, C, and D sites, and oxygen atoms, respectively. (b) Millimeter wave absorption spectrum obtained from THz-time domain spectroscopy measurement. (c) Preparation process of the ε-iron oxide dispersion and ε-iron oxide film. (d) 3D topological AFM image of the magnetic film. (e) Magnetic hysteresis loop of the film when the external magnetic field is applied to the out-of-plane direction. The data in the figure are for the sample with a composition of x=0.23 and y=0.04.

Click to enlarge

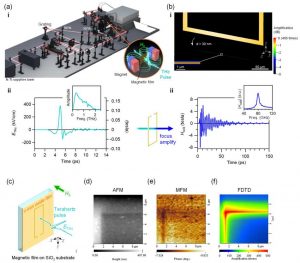

Additionally, an intense millimeter-wave generator was constructed using terahertz light as a light source, and a millimeter-wave focusing ring [5] was designed using electromagnetic field analysis simulation [6] and fabricated on the surface of the magnetic film [6] to focus the millimeter wave corresponding to the resonance frequency of GTC-type ε-iron oxide. As shown in Figure 3, the magnetization direction of the film was aligned along the +Z-direction. Then, an external magnetic field of 3.4kOe, slightly weaker than the coercive field value of 4.9kOe, was applied toward the opposite direction (−Z-direction). The sample was irradiated by a focused millimeter wave.

Figure 3 :Setup of focused millimeter wave–assisted magnetization reversal,

design of the focusing ring, and the demonstration experiment.

Click to enlarge

(a) (i) Schematic of the intense terahertz light generation from the LiNbO3 crystal. Inset shows the configuration of the film, external magnetic field (H0), and terahertz pulse. (ii) Observed electric field of the terahertz pulse in the time domain and its Fourier-transformed spectrum. (b) (i) Electromagnetic field analysis of the Au ring (735-μm long and 265-μm wide with a 14.7-μm ring width, a 58.8-μm gap, and a 0.1-μm thickness). Colored areas show the intensity of the millimeter wave magnetic field (Hmilli) at 30nm below the focusing ring. (ii) The calculated time dependence of Hmilli at the inner corner of the ring. Inset is the frequency spectrum of ǀHmilliǀ. (c) Schematic configuration of the ring on the magnetic film, and directions of H0 and terahertz pulse. (d) AFM image at the corner of the ring after 1-shot terahertz pulse irradiation under H0 of 3.4 kOe. Color scale indicates the height. (e) MFM image of the same position as d. Color scale indicates the magnetic fluxes going out of (white) and into (black) the page, corresponding to the N- and S-poles, respectively. (f) Calculated distribution of Hmilli at the inner corner of the ring.

The atomic force microscopy (AFM) [7] image of the sample after irradiation of the focused-millimeter wave showed the geometry of the ring. In the magnetic force microscopy (MFM) image, a dark shadow was observed near the focusing ring. The observed MFM image agrees well with the magnetic field distribution map simulated by electromagnetic field analysis, indicating that the magnetization was flipped by the assistance of the focused-millimeter wave. This is the first reported observation of a permanent magnetic pole flip by millimeter wave irradiation.

As an additional demonstration, a magnetic film placed face-to-face with the millimeter wave–focusing ring fabricated on Si wafer was irradiated with a millimeter wave. In the MFM image of the magnetic film after irradiation of the focused-millimeter wave, magnetization reversal was observed at the millimeter wave focused area.

To understand the spin dynamics of F-MIMR, the time evolution of all of the spins in an epsilon iron oxide nanoparticle were calculated using the stochastic Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert model [8]. Simulation results showed that magnetization reversal instantly occurs by irradiating a millimeter wave of the resonance frequency.

Millimeter wave magnetic recording technique enables to reduce the particle size of the magnetic material and solve the magnetic recording trilemma, leading to the increase of the recording capacity. The transition energy of the millimeter wave is ca. 1/5000 compared to that visible light. Therefore, heat-up is avoided in millimeter wave–assisted magnetic recordings, which is very important for magnetic tapes that use organic resin for the base film.

The present research was supported in part by the Advanced Research Program for Energy and Environmental Technologies/Development of a millimeter wave assisted magnetic recording method for magnetic tapes project (Ohkoshi Laboratory, The University of Tokyo / Nakajima Laboratory, Osaka University / Recording Media Research & Development Laboratories, FujiFilm Corporation) commissioned by NEDO of METI.

Glossary:

[1] Magnetic tapes : Magnetic tapes are the earliest known magnetic recording media (since the 1950s). Japanese companies have monopolized the production of tape media and, nowadays, magnetic tapes are mainly used as the recording media for archiving. Due to the guarantee for long-term recording and low cost, demands for magnetic tapes are growing rapidly in a variety of areas, including insurance companies, banks, broadcasting stations, and web service companies.

[2] Epsilon iron oxide (ε-Fe2O3): Ohkoshi and his colleagues synthesized a single phase of epsilon iron oxide in 2004 by nanoparticle synthesis method. They reported that epsilon iron oxide possesses a crystal structure different from the conventional phases such as gamma (γ) and alpha (α) phases, and exhibits the largest coercive field among metal oxides at room temperature (20 kOe). In addition, epsilon iron oxide has been highlighted as one of the candidates for the next generation of magnetic particles for magnetic tapes in the roadmap of the information storage industry consortium (INSIC), a consortium of the magnetic tape industry.

[3] Beyond 5G: Beyond 5G is the sixth and subsequent communication standard following the fifth generation of mobile communication system (5G; 3.7GHz, 4.5GHz, 28GHz in Japan), which began to be used in 2019. Millimeter waves, which are higher frequency electromagnetic waves, are expected to be used in beyond 5G networks.

[4] Millimeter waves: Millimeter waves are electromagnetic waves with a wavelength of 1mm to 10mm and a frequency range of 30 to 30 GHz. At present, millimeter-wave car radars are widely used, and practical applications of millimeter waves for wireless communication are being promoted as a next-generation high-speed wireless communication system. Epsilon iron oxide absorbs high-frequency millimeter-waves due to the precession of the magnetization, and is expected as a millimeter-wave absorber for high-speed wireless communications and automated driving support systems.

[5] Focusing ring: Focusing ring is a metallic ring with a gap. When electromagnetic waves, such as terahertz light, are irradiated to the focusing ring, a circumferential current flows, causing a resonant phenomenon that enhances the intensity of the electromagnetic waves at a particular frequency.

[6] Electromagnetic field analysis simulation: Electromagnetic field analysis is a simulation that theoretically calculates the electric and magnetic field distributions generated by electromagnetic waves.

[7] Atomic force microscopy and magnetic force microscop; Atomic force microscopy detects the interatomic force between the probe and the sample to show the geometries of the sample surface. On the other hand, magnetic force microscopy detects the magnetic force between the probe and the sample to show the magnetic state of the sample surface.

[8] Stochastic Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert mode: Stochastic Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert model is a theoretical model that incorporates stochastic noise as temperature effects into the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation, an equation that describes the precession of the magnetization in magnetic materials. F-MIMR was theoretically demonstrated using a model taking into account all of the individual spin movements in the nanoparticle.

Article: Magnetic‐Pole Flip by Millimeter Wave

Advanced Materials has published an article written by Shin‐ichi Ohkoshi, Marie Yoshikiyo, Kenta Imoto, Kosuke Nakagawa, Asuka Namai, Department of Chemistry, School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 7‐3‐1 Hongo, Bunkyo‐ku, Tokyo, 113‐0033 Japan, Hiroko Tokoro, Department of Chemistry, School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 7‐3‐1 Hongo, Bunkyo‐ku, Tokyo, 113‐0033 Japan, and Department of Materials Science, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1‐1‐1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305–8577 Japan, Yuji Yahagi, Department of Materials Science, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1‐1‐1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305–8577 Japan, Kyohei Takeuchi, Fangda Jia, Seiji Miyashita, Department of Physics, School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 7‐3‐1 Hongo, Bunkyo‐ku, Tokyo, 113‐0033 Japan, Makoto Nakajima, Hongsong Qiu, Kosaku Kato, Institute of Laser Engineering, Osaka University, 2‐6 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka, 565–0871 Japan, Takehiro Yamaoka, Analysis Systems Solution Development Dept., Metrology and Analysis Systems Product Div., Hitachi High‐Tech Corporation, 3‐2‐1 Sakado, Takatsu‐ku, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, 213‐0012 Japan, Masashi Shirata, Kenji Naoi, Koichi Yagishita, and Hiroaki Doshita, Recording Media Research and Development Laboratories, FujiFilm Corporation, 12‐1, Ohgi‐cho 2‐Chome, Odawara‐shi, Kanagawa, 250‐0001 Japan.

Abstract: “In the era of big data and the IoT, data archiving is a key technology. From this viewpoint, magnetic recordings are drawing attention because they guarantee long‐term data storage. To archive an enormous amount of data, further increase of the recording density is necessary. Herein a new magnetic recording methodology, ‘focused‐millimeter‐wave‐assisted magnetic recording (F‐MIMR),’ is proposed. To test this methodology, magnetic films based on epsilon iron oxide nanoparticles are prepared and a focused‐millimeter‐wave generator is constructed using terahertz (THz) light. Irradiating the focused millimeter wave to epsilon iron oxide instantly switches its magnetic pole direction. The spin dynamics of F‐MIMR are also calculated using the stochastic Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert model considering all of the spins in an epsilon iron oxide nanoparticle. In F‐MIMR, the heat‐up effect of the recording media is expected to be suppressed. Thus, F‐MIMR can be applied to high‐density magnetic recordings.“

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter