R&D: Discovery May Lead to New Materials for Next-Gen Storage

Army-funded research demonstrates emergent chirality in polar skyrmions for first time in oxide superlattices.

This is a Press Release edited by StorageNewsletter.com on May 21, 2019 at 2:47 pmFrom CCDC Army Research Laboratory Public Affairs

Research funded in part by the U.S. Army identified properties in materials that could one day lead to applications such as more powerful data storage devices that continue to hold information even after a device has been powered off.

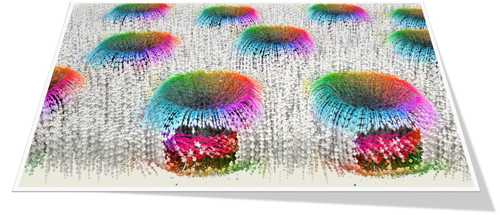

Army funded research discovery may allow for development of novel device structures that can be used to improve logic/memory, sensing, communications, and other applications for the Army as well as industry. Image demonstrates simulation of emergent chirality in polar skyrmions for the first time in oxide superlattices.

(Courtesy of Xiaoxing Cheng, Pennsylvania State University; C.T. Nelson, Oak Ridge National Laboratory;

and Ramamoorthy Ramesh, University of California, Berkeley)

A team of researchers led by Cornell University and the University of California Berkeley made a discovery that opens up a plethora of materials systems and physical phenomena that can now be explored.

The scientists observed what’s known as chirality for the first time in polar skyrmions in an exquisitely designed and synthesized artificial material with reversible electrical properties. Chirality is where two objects, like a pair of gloves, can be mirror images of each other but cannot be superimposed on one another. Polar skyrmions are textures made up of opposite electric charges known as dipoles.

Researchers had always assumed that skyrmions would only appear in magnetic materials, where special interactions between magnetic spins of charged electrons stabilize the twisting chiral patterns of skyrmions. When the team discovered skyrmions in an electric material, they were astounded, they said.

The combination of polar skyrmions and these electrical properties may allow for the development of novel devices that are of significant interest to the Army, especially using the chirality as a parameter that can be manipulated.

“Now that we know that polar/electric skyrmions are chiral, we want to see if we can electrically manipulate them,” said Dr. Ramamoorthy Ramesh, co-principal investigator of this project. “If I apply an electric field, can I turn each one like a turnstile? Can I move each one, one at a time, like a checker on a checkerboard? If we can somehow move them, write them, and erase them for data storage, then that would be an amazing new technology.“

Researchers published their findings in the journal Nature.

“This ground-breaking discovery can be used in the future to develop device structures that can be used to improve logic/memory, sensing, communications, and other applications for the Army as well as industry,” said Dr. Pani (Chakrapani) Varanasi, chief, materials science division, Army Research Office, an element of U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Command’s Army Research Laboratory.

When the team began the study in 2016, they had set out to find ways to control how heat moves through materials. They fabricated a special crystal structure called a superlattice from alternating layers of lead titanate (an electrically polar material, whereby one end is positively charged and the opposite end is negatively charged) and strontium titanate (an insulator, or a material that doesn’t conduct electric current).

The research team started to explore the synthesis of artificially designed and structured oxides, with the goal to explore emergent phenomena. Emergent phenomena are pervasive in nature – fish swimming in a school, birds flying in formation, the emergence of crowd and mobs are all examples of how interactions of discrete objects (fish, birds, humans) can lead to unexpected collective behavior. Materials can also exhibit such emergent behavior, especially when placed under constraints.

When the scientists took scanning transmission electron microscopy measurements of the artificially engineered lead titanate/strontium titanate superlattice, they saw something strange that had nothing to do with heat: Bubble-like formations had cropped up all across the material. Lead titanate is a well-known ferroelectric material, while strontium titanate, its sister compound is not ferroelectric at room temperature. Ferroelectric are materials that have a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by the application of an external electric field.

Those bubbles, it turns out, were polar skyrmions.

While using sophisticated scanning transmission electron microscopy at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry and at the Cornell Center for Materials Research, David Muller, Cornell University, took atomic snapshots of skyrmions’ chirality at room temperature in real time. The researchers discovered that the forces placed on the polar lead titanate layer by the nonpolar strontium titanate layer generated the polar skyrmion bubbles in the lead titanate.

“Materials are like people,” Ramesh said. “When people get stressed, they respond in unpredictable ways. And that’s what materials do too: In this case, by surrounding lead titanate by strontium titanate, lead titanate starts to go crazy – and one way that it goes crazy is to create polar textures like skyrmions instead of being uniformly polarized.“

“This work has enabled the discovery of a fundamentally new phenomena in oxide superlattices,” Schlom said. “We now have a template based on epitaxy to create many other science universes. For example, we can start to look at spin-charge coupling in such superlattices; work on this is already underway.“

The researchers also plan to study the effects of applying an electric field on the polar skyrmions.

Researchers from Pennsylvania State University and Oak Ridge National Laboratory also contributed to the study.

Additionally, the Department of Energy Office of Science supported this research with additional funding provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation‘s EPiQS Initiative, the National Science Foundation, the Luxembourg National Research Fund, and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

The CCDC Army Research Laboratory (ARL) is an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command. As the Army’s corporate research laboratory, ARL discovers, innovates and transitions science and technology to ensure dominant strategic land power. Through collaboration across the command’s core technical competencies, CCDC leads in the discovery, development and delivery of the technology-based capabilities required to make Soldiers more lethal to win our Nation’s wars and come home safely. CCDC is a major subordinate command of the U.S. Army Futures Command.

Article: Observation of room-temperature polar skyrmions

Nature has published an article written by S. Das, Y. L. Tang, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, Z. Hong, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, M. A. P. Gonçalves, Materials Research and Technology Department, Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST), Esch/Alzette, Luxembourg, M. R. McCarter, Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, C. Klewe, Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, K. X. Nguyen, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, F. Gómez-Ortiz, Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y Física de la Materia Condensada, Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, Spain, P. Shafer, Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, E. Arenholz, Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, V. A. Stoica, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, S.-L. Hsu, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, and National Center for Electron Microscopy, Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, B. Wang, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, C. Ophus, National Center for Electron Microscopy, Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, J. F. Liu, Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, C. T. Nelson, Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, USA, S. Saremi, B. Prasad, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, A. B. Mei, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, D. G. Schlom, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, and Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science, Ithaca, NY, USA, J. Íñiguez, Materials Research and Technology Department, Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST), Esch/Alzette, Luxembourg, and Physics and Material Science Research Unit, University of Luxembourg, Belvaux, Luxembourg, P. García-Fernández, Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y Física de la Materia Condensada, Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, Spain, D. A. Muller, Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science, Ithaca, NY, USA, and School of Applied and Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, L. Q. Chen, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, J. Junquera, Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y Física de la Materia Condensada, Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, Spain, L. W. Martin, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, and Materials Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, and R. Ramesh, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, Materials Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA, and Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Abstract: “Complex topological configurations are fertile ground for exploring emergent phenomena and exotic phases in condensed-matter physics. For example, the recent discovery of polarization vortices and their associated complex-phase coexistence and response under applied electric fields in superlattices of (PbTiO3)n/(SrTiO3)n suggests the presence of a complex, multi-dimensional system capable of interesting physical responses, such as chirality, negative capacitance and large piezo-electric responses. Here, by varying epitaxial constraints, we discover room-temperature polar-skyrmion bubbles in a lead titanate layer confined by strontium titanate layers, which are imaged by atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy. Phase-field modelling and second-principles calculations reveal that the polar-skyrmion bubbles have a skyrmion number of +1, and resonant soft-X-ray diffraction experiments show circular dichroism, confirming chirality. Such nanometre-scale polar-skyrmion bubbles are the electric analogues of magnetic skyrmions, and could contribute to the advancement of ferroelectrics towards functionalities incorporating emergent chirality and electrically controllable negative capacitance.“

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter