Practical Guide for GDPR Compliance – Osterman Research

Consequences of getting it wrong are significant.

This is a Press Release edited by StorageNewsletter.com on August 3, 2017 at 2:40 pmThis white paper was published on July 2017 by Osterman Research, Inc. and sponsored by Druva, Inc.

A Practical Guide for GDPR Compliance

Executive summary

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been approved by the European Union and, once it comes into force in May 2018, will give data subjects significant new rights over how their personal data is collected, processed, and transferred by data controllers and processors. It demands significant data protection safeguards to be implemented by organizations. The time to get ready is now, as the consequences of getting it wrong are significant.

Key takeways

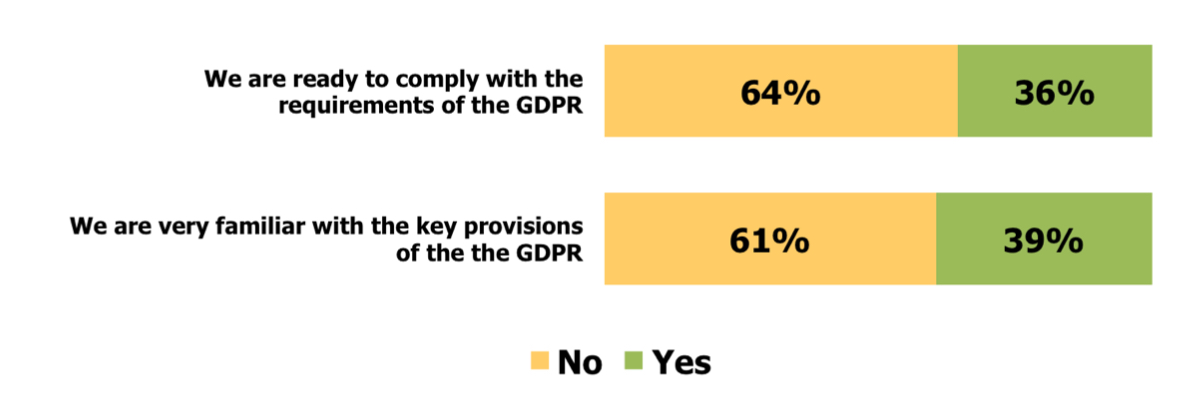

• Most organizations are not yet adequately prepared for compliance with the GDPR, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Organizational Preparedness for the GDPR

• The GDPR is a sweeping and far-reaching update to the European Directive on Data Privacy from 1995. It harmonizes data protection requirements across all 28 member states, introduces new rights for data subjects, and applies extra-territorially to any organization controlling or processing data on natural persons in the European Union.

• Complying with GDPR is not optional. If your organization controls or processes personal data on natural persons in the European Union, GDPR almost certainly applies to you. There are a whole host of requirements and mandates that need to be in place when GDPR comes into force, not least of which is that when a data breach occurs, the local data protection authority and all affected data subjectsi must be notified within 72 hours.

• GDPR requires data controllers and processors to implement both organizational and technical safeguards to ensure the rights and freedoms of data subjects are not compromised. Organizational safeguards include data protection impact assessments, data protection by design for both structured and unstructured data, and the appointment of a data protection officer who reports to the highest level of the organization.

• Technical safeguards include pseudonymization, encryption, and various capabilities for identifying and blocking data breaches, ensuring data security, and automatically identifying and classifying personal data, among others. It is important to note that a data breach according to the GDPR also includes ‘accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorized disclosure of, or access to, personal data transmitted, stored or otherwise processed’, and so preventing unauthorized use or access must also be considered as a key element of GDPR compliance.

• The deadline for being compliant with GDPR is rapidly approaching, and the transitionary period between the earlier Directive and the new Regulation is on now. Once the Regulation goes into force on May 25, 2018, organizations will be expected to comply immediately from that date.

• Being non-compliant with GDPR will be very expensive. In addition to other financial consequences, there are two tiers of regulatory fines, the more expensive of which is a fine of up to €20 million or 4% of the annual worldwide turnover for the organization, whichever is higher. However, there is a need for continual compliance with the GDPR, since a failed audit can have damaging financial consequences. Consult Hyperion has estimated that European financial firms alone may face GDPR-related fines of $5.3 billion in the first three years after the GDPR becomes effectiveii.

Why is GDPR so important

The GDPR is the newly harmonized European-wide regulation that mandates the protection of data about people living in the European Union, by every organization that controls or processes data on people in the EU, regardless of where that organization is located around the world. Its correct name is Regulation (EU) 2016/689, and it updates, replaces, and extends the protections previously afforded through the earlier 1995 directive on data privacy (Directive 95/46/EC). Protections for personal data of individuals involved in criminal proceedings are excluded from the GDPR; the protection regime for such circumstances are outlined in a complementary directive (Directive (EU) 2016/680), and is beyond the scope of this paper.

The new GDPR is important, for several reasons:

• It almost certainly applies to you. If your organization controls or processes data on people living in the European Union – even if your organization is not located in the EU – it applies.

• It has a significant bite, in the form of sky-high regulatory fines for non-compliance. If you meet the test of applicability for the GDPR, you cannot opt out of complying.

• It touches every data process in organizations that collects or processes personal data on people, and it covers both direct and indirect data identifiers in every data system.

• It forces organizations to know and understand their data from a 360-degree perspective. Organizations that process EU citizen data will need to know where it is being processed, who is processing and storing it, and demonstrate the ability of ‘erasure’ on it no matter where it lives.

• It demands greater transparency with people on how their data is collected and processed, and introduces notification requirements when personal data is breached. There are reputational consequences of getting this wrong, particularly in light of the fact that during the previous 12 months, 47% of the organizations surveyed for this white paper have suffered a breach of customers’ or other personal data, employees’ personal data, corporate intellectual property, or other sensitive or confidential information.

• There is now no cost associated with requests from data subjects, which means that it is now more likely that many more individuals will be making demands about the information that is held about them.

• You are running out of time. GDPR was signed into law just over a year ago (via publication in the EU Official Journal in early May 2016), and will be enforced starting May 25, 2018.

The earlier Directive on data privacy came into force in 1995, just as the Internet was beginning its adoption trajectory. One of the driving reasons for the new GDPR was to strengthen data protection requirements in light of an increasingly global and interconnected world, and the regulators took an interesting path. Instead of regulating territorially on organizations within the EU, it shifted the focus to where data subjects reside. This subtle shift means GDPR applies to the personal data of data subjects in the EU (territorially), but has borderless applicability to organizations. The test is no longer whether your organization is in the EU, but rather whether your organizations collects or processes the personal data of people who are in the EU.

Specifically:

• Article 23 lists key tests of applicability for organizations not located in the EU. The primary test is that “the processing activities are related to offering goods or services to such data subjects irrespective of whether connected to a payment.” However, “mere accessibility” to an organization’s website or email address is not sufficient to establish the intent of offering goods or services; whereas factors such as the use of a currency generally used in a member state, and listing customers located in the Union on your website, does ascertain that intention.

• Article 24 offers a second key test of applicability: when an organization controls or processes data for monitoring the behavior of people that happens within the EU. Specific actions include tracking on the internet, “profiling” based on past actions, and “analyzing or predicting … personal preferences, behaviors and attitudes.” If your organization does this for people within the EU, GDPR applies regardless of where you are located.

• With the UK’s vote in 2016 to leave the European Union, there has been some discussion about the applicability of GDPR. There are two answers. First, the Data Protection Act is the UK law for data protection, and if the UK does leave the Union, the GDPR will not apply to data subjects and personal data within the UK. Second, the GDPR does apply to Europe, and any UK firm that wants to sell into the EU Single Market will have to comply with GDPR requirements. Individual firms can upgrade their data protection approaches to the GDPR mandates, in addition to whatever regulatory reform is undertaken in the UK to provide equivalent data protection standards.

In closing, GDPR is coming fast, it almost certainly applies to your organization, and the consequences of getting it wrong are severe. Equally, however, are the positive consequences of getting it right, including a strong foundation for working with businesses in Europe, a clear understanding of consumer preferences, and strong internal data protection and security controls that foster trust with customers and partners alike.

On the privacy of personal data in the EU

‘Privacy’ of personal data has been an essential concept in European law since 1995, when the Directive on data privacy was introduced. As a directive, however, it did not directly mandate data privacy protections for EU member states, as each state had the freedom to include the recommended privacy protections in their own laws. This freedom led to nuances and differences in data privacy regulations across member states, making it complex for firms to meet compliance requirements.

The new GDPR is different. First, it is a regulation – and not a directive – for all EU member states. Member states don’t have to enshrine GDPR into their own laws; it already applies to all of them. Second, the more limited focus on ‘data privacy’ in the earlier directive has given way to a broader emphasis on “data protection” in GDPR; this higher standard demands more of organizations everywhere.

The question as to ‘why’ privacy and protection of personal data is necessary is addressed in Article 75 of GDPR. The view is that lack of privacy and protection increases “risks to the rights and freedoms of natural persons … which could lead to physical, material or non-material damage.” Specific examples listed include discrimination, identity theft, fraud, financial loss, and loss of confidentiality of personal data, among others.

What is ‘personal data’ anyway?

Personal data is the first definition given in Article 4: “any information related to an identified or identifiable natural person” (called a data subject throughout the GDPR). Direct identifiers include name, ID number, and online identifiers (e.g., email address), and indirect identifiers include location data and various types of identity. The personally identifiable information (PII) that will be relevant in the context of the GDPR includes data subjects’ biometric data, network identifiers, images, hobbies, political preferences, religious preferences, sexual orientation and other information about EU residents.

The key test is whether direct and indirect personal data can be used to uniquely identify a natural person: while the person’s name obviously can, so can the combination of indirect identifiers. For example, a study in the United States found that date of birth, zip code, and gender allowed for the unique identification of 87% of Americans, hence the need to afford indirect identifiers the same level of protection as direct ones.iii

The Directive of 1995 and the Regulation of 2016 are directionally the same, but the Regulation demands a significant uplift in data protection.

For example:

• Data subjects acquire many new rights, including the right to be forgotten, the right to move their data to another provider, and the right of access to verify data correctness and the processing activities his or her data are subjected to.

• Organizations that control or process personal data must meet elevated protection mandates, including gaining specific consent from data subjects, record keeping, notification of data breaches, and having the organizational and technical means to respond to the rights of data subjects in a timely manner.

• Under the Directive, data processors only had responsibilities insofar as they were demanded through contractual agreements with data controllers. Under GDPR, processors now have direct obligations to implement appropriate security measures, maintain records of processing activities, and meet data breach notification requirements.

Drivers for introducing GDPR

Several factors drove the development of the GDPR for Europe, including:

• Modernizing the data protection laws to take account of the Internet, digital marketing, social networks, and the whole plethora of data tracking capabilities currently on offer and coming due to technological advances since the Directive was introduced in 1995.

• Harmonizing the legal framework for data protection across Europe, moving from separate regulations in member states to a Digital Single Market with common standards and rules for all. The European-wide regulation simplifies compliance for organizations operating in multiple States.

• Driving a stronger culture of data protection and security into the heart of organizational data processes. The regulation makes clear the requirements on organizations controlling or processing personal data, and demands stronger measures to protect data subjects and reduce mistakes in handling personal data.

• Leveling the playing field so organizations outside of the Union can’t claim immunity from data protection requirements when handling personal data of EU natural persons. The Directive applied territorially to organizations; the Regulation applies territorially to the personal data of data subjects, and to organizations regardless of location.

• Impacting global legal frameworks on data protection, by making GDPR apply to any organization controlling or processing personal data on data subjects in the EU, and by demanding equivalent data protection standards from other countries and jurisdictions wanting to trade with the EU single market. We have previously commented that the GDPR should be more appropriately called the “Global” Data Protection Regulation, given its legal impacts.

Compliance time frame

The European Commission introduced its data protection reform in early 2012, and after four years of negotiations the GDPR was adopted by the European Council and European Parliament in April 2016. It was published in the EU Official Journal in early May last year, and comes into force on May 24, 2018. It will apply from May 25, 2018. There is no transitionary period as such after coming into force; that time is the two-years between May 2016 and May 2018, of which we are already more than half way through.

Brexit and GDPR

It is important to note that regardless of the implementation of Brexit (the UK’s exit from the EU), the GDPR will continue to apply to subjects and organizations within the UK. The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has clearly stated that the GDPR will be the minimum standard of protection for personal data.

Specifically, the ICO has stated thativ:

• “The GDPR will apply in the UK from 25 May 2018. The government has confirmed that the UK’s decision to leave the EU will not affect the commencement of the GDPR.”

• “The GDPR applies to ‘controllers’ and ‘processors’. The definitions are broadly the same as under the [UK Data Protection Act] – i.e., the controller says how and why personal data is processed and the processor acts on the controller’s behalf. If you are currently subject to the DPA, it is likely that you will also be subject to the GDPR.”

• “If you are a processor, the GDPR places specific legal obligations on you; for example, you are required to maintain records of personal data and processing activities. You will have more legal liability if you are responsible for a breach. These obligations for processors are a new requirement under the GDPR. However, if you are a controller, you are not relieved of your obligations where a processor is involved – the GDPR places further obligations on you to ensure your contracts with processors comply with the GDPR.“

Non-complaince penalties

There are major penalties for non-compliance with GDPR, and these are set in two tiers (Article 83). Administrative fines of up to €10 million or 2% of the total worldwide annual turnover (that’s revenue, not profit) for the organization can be levied for various infringements, such as not enacting data protection by design and by default (Article 25), failing to keep adequate records of processing activities (Article 30), and not ensuring appropriate security of processing (Article 32), among many others. The failure of an audit of GDPR compliance, which will be a more common event than a violation of the GDPR itself, can also result in penalties.

The higher tier of fines – which are up to €20 million or 4% of total worldwide annual turnover – is for more serious wrongdoing, such as not following the basic principles of collecting and processing data (Article 6), failing to acquire adequate consent from a data subject (Article 7), and not providing data subjects with their rights (Articles 12 to 22).

Both penalty level are “whichever is higher” between the Euro figure and the percentage amount, so an organization with a worldwide turnover of €10 billion could face a fine of €400 million under the second tier. Note that data subjects themselves also have the right to seek damages through a civil court from an organization that fails to protect their personal data.

Essential requirements of GDPR

Let’s briefly review the essential requirements of the GDPR.

You must:

• Have a legal basis for controlling and processing personal data (Article 6). Legal grounds include direct consent from the data subject, for performance of a contract with the data subject, compliance with a legal obligation of the controller, protecting the vital interests of a data subject, and the legitimate interests of the controller. It is essential to be very clear on the specific legal basis for collecting and processing personal data, because some rights held by data subjects apply only to data held under one or two legal grounds, for example. While the ‘legitimate interests’ basis appears to give wide sway to organizations, there are various provisions that limit its applicability, such as taking into account the context in which the data was collected and the relationship between the data subject and the controller.

• Collect and process personal data only for lawful purposes, and protect it at all times. Required protections include preventing accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, processing, disclosure, access, and alteration. Data subjects have significant rights and freedoms under GDPR, and these must be upheld through appropriate organizational and technological measures.

• Maintain documentation of all data processing activities (Article 30). Required details include the purposes of the processing, categories of data subjects and personal data involved, categories of recipients, safeguards on any data transfers, and if possible, time limits for erasure. A description of technical and organizational security measures is also required. These records are to be kept in writing or electronic form, and available for audit and review by the supervisory authority on request. Organizations with fewer than 250 employees are excluded from these documentation requirements, with some provisos.

• Perform an assessment on the risks to the rights and freedoms of controlling and processing personal data, and develop organizational and technological mitigations for the identified risks. The risk assessment has to include any third-party relationships for data held and processed on your behalf.

• Be able to demonstrate compliance with the GDPR, through organizational and technical measures, and the on-going assessment of the strength and suitability of these measures (Article 25). Demonstrating compliance includes having policies on how to protect data under your control, an up-to-date assessment of risks to personal data (e.g., unauthorized or overprivileged access), workable technical measures that enforce protection (such as encryption), rules on transferring data to other countries, a staff training and awareness program, the means to identify and investigate data breaches, and the means to respond promptly to data access requests by data subjects, among others. All of these measures are on-going: they need to work at all times, and having the means to verify the effectiveness of implemented measures is essential. Certification mechanisms are mentioned throughout the GDPR as well, highlighting the on-going nature of compliance. Overall, the clear intent of the GDPR is that personal data is actually protected, not merely that organizations implement data protection tools.

• Meet the elevated standard of consent, anytime consent is the legal basis for processing data (Article 7). Consent means “any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subjects’ wishes … by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, [that] signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her” (as defined in Article 4(11)). Consent cannot be implicit, the result of pre-ticked boxes, or silence. Consent must be documented (which means the data controller must be able to produce evidence that consent was given). And among other stipulations, consent cannot be bundled (it must be given for each specific processing operation and purpose), and the data subject must be able to withdraw consent just as easily as they gave it. This elevated standard of consent applies to consent gained after GDPR comes into force in late May 2018, as well as to any pre-GDPR consent indications that will be used after GDPR goes live.

• Minimize the amount of personal data processed, a principle called data minimization (Article 5(c)). The intent of this requirement is that superfluous or extraneous personal data that is not required for a specific processing activity are not collected or processed. Article 25 takes this requirement further, in addressing the requirement of “data protection by design and by default.” Once personal data is no longer required for current data processing activities, it should be minimized through pseudonymization (a process of replacing direct and indirect identifiers with near-meaningless values, although these can be reidentified through specific means) or the data should be erased.

• Notify the supervisory authority of a data breach within 72 hours of becoming aware of the breach (Article 33), and under certain circumstances, notify every data subject whose data was breached as well (Article 34). A breach notification is not required to the supervisory authority if the breach is “unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons,” nor to data subjects if the breach won’t result in a “high risk” to their rights and freedoms. For example, if the breached data was encrypted with a sufficiently strong encryption mechanism, data breach notifications are not required.

• Appoint a data protection officer (Article 37), who can be an employee for one organization, a representative for a group of organizations, or an external consultant. This is mandatory for public authorities, and for organizations that meet one or both of two tests: core activities “consist of processing operations which … require regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale,” or that special categories of data are processed on a large scale. The data protection officer (DPO) must have “professional qualities,” “expert knowledge of data protection law and practices,” and the ability to perform the tasks detailed in Article 39. Such obligations include informing and advising the controller and processor (and employees) of their obligations under GDPR, monitoring compliance, and being the liaison person with the supervisory authority. The DPO must “directly report to the highest management level” (Article 38), and is to be afforded independence in carrying out his or her tasks.

• Carry out a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) for envisaged processings that are “likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms” of data subjects, and secure the participation of the designated data protection officer in the assessment (Article 35). High risks cover activities like automated processing and profiling, decisions that produce legal effects for people, large scale processing of “special categories of data,” and the “systematic monitoring of a publicly accessible area on a large scale.” The intent of such assessments is to force the pre-processing evaluation of what is actually necessary, how the processing activity could harm data subjects, and how to develop organizational and technical mitigations to reduce any foreseen harm. Under some circumstances, organizations must consult with the supervisory authority prior to undertaking the processing itself, and wait until the supervisory authority has ruled the processing activity to be lawful (Article 36).

• Ensure the protection of data during processing activities, through the implementation of “appropriate technical and organizational measures” (Article 25). These protection safeguards are to be implemented when determining how to carry out a processing, and at the actual time of carrying out the processing activity. The safeguards required are to be in proportion to the risks to the rights and freedoms of data subjects. Article 32 lists technical and organizational security measures such as pseudonymization, encryption, processing system confidentiality, integrity and resilience, and a regular testing process for ensuring the security measures actually work.

• Abide by specific conditions when processing special categories of data. Article 9(1) states the general prohibition: “Processing of personal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation shall be prohibited.” Article 9(2) then lists 10 exclusions to the general rule. Given the elevated harm that can accrue to individuals based on these special categories of data, greater protections are mandated. GDPR recognizes that the use of data may be sensitive, and hence seeks to limit such usage, which is why data protection impact assessments are generally necessary for processing special categories of data, the data protection officer must be across such processing, and consultation with the supervisory authority is required.

• Respond promptly to requests from data subjects about the personal data you control, process, or transfer about him or her (Article 15). The data subject has the right of access to know the purposes of the processing, categories of personal data processed, recipients or categories of recipients the data will or have been disclosed to, how long the data will be stored, their right to rectification or erasure, and more. If the personal data is subjected to automated decision-making and profiling, you have to provide “meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing for the data subject.” The first request from a data subject must be fulfilled free of charge, although “a reasonable fee based on administrative costs” can be levied for “further copies.” Article 63 adds that the data subject should be able to “exercise [this] right easily and at reasonable intervals, in order to be aware of, and verify, the lawfulness of the processing.” Article 63 goes on to suggest the use of a “secure system” that gives the data subject direct access to his or her personal data.

• Update and correct any inaccurate personal data held about a data subject, by various means including a supplementary disclosure from the data subject (Article 16). This is the flip side of the data subjects’ right to rectification. Organizations will need tight integration across all data systems and processes to ensure data updated in one system is automatically and correctly updated across all other locations too.

• Permanently erase any personal data about a data subject under specified conditions (Article 17). These include the withdrawal of consent by the data subject (where consent was the original lawful basis for collection and processing), the data has been unlawfully processed, and the data subject objects to the processing of their personal data and there are no other legitimate grounds for continuing to process the data. If the data has been made public by the controller or processor, ‘reasonable steps’ need to be taken to inform other controllers and processors of the erasure request.

• Be able to temporarily restrict the processing of personal data on request from the data subject under certain conditions (Article 18). These include contested accuracy, unlawful processing but erasure is not requested, and the data subject’s need for the personal data for legal claims but where further processing is not necessary. Article 67 outlines several methods for restricting processing, and requires that this fact “should be clearly indicated in the system.”

• Supply personal data concerning a data subject in a “structured, commonly used and machine-readable format” in response to a request for data portability (Article 20). This requirement is limited to the personal data the data subject “has provided to a controller,” and the data subject can request the controller to transmit the data to a new data controller “without hindrance” or in good faith. There are various exclusions noted in Article 20, such as where other lawful grounds apply to future processing activities.

• Have alternative methods available for making decisions about people rather than just automated processing and profiling, such as human intervention (Article 22). There are several exceptions to this mandate, such as the necessity of processing related to contractual matters, exemptions under Union or Member State law, and where the data subject’s explicit consent has been given (and not withdrawn). Article 22 makes it clear, however, that whatever happens, the data subject’s rights and freedoms must be safeguarded.

• Prevent data from being transferred outside of the EU to “a third country or to an international organization” unless specific protections are in place (Article 44). These protections can be either an adequacy decision by the European Commission (the target recipients have an adequate level of data protection; Article 45), or the controller or processor has appropriate safeguards in place and legal remedies available (Article 46), such as Binding Corporate Rules (Article 47), among others.

• Ensure additional restrictions are in place to safeguard the handling of personal data of children when services are offered directly to children (Article 38). Language aimed directly at children must be “in such a clear and plain language that the child can easily understand,” (Article 58) and consent is required from “the holder of parental responsibility over the child” for children under the age of 16 (Article 8), although Member States can lower this to 13 years. One strong implication of this requirement is the ability to verify proof of age.

It should be clear from the above “brief review” that the GDPR demands many significant undertakings from all organizations controlling or processing personal data on natural persons in the European Union.

Summary

The GDPR will be enforced beginning in less than 11 months from the publication date of this white paper. Every organization that maintains data on EU residents will need to ensure that they have the appropriate capabilities in place to ensure compliance with the varied aspects of the GDPR. Not complying will be potentially very damaging and, if the EU follows through on its promised fine structure, very expensive.

There are three primary imperatives that should drive decision makers to give the GDPR an extremely high priority until compliance has been assured:

• Get your data ducks in a row

Every organization that maintains data on EU residents must undertake a significant re- examination of its data strategy with regard to its personal and sensitive data on these individuals. The specific requirements must be understood, planned for, and technology approaches implemented to address problems, strengthen policies and protections, and protect against things like data breaches and an inability to comply with the provisions of the GDPR. Data protection must be “by design and by default.”

• Many firms will have to play catch up

Organizations in the EU have lived with the general notion of the GDPR for more than two decades, but non-EU firms are largely unprepared for the implications of such a rigorous approach to data protection. Consequently, non-EU firms will need to come up to speed rapidly in order to protect against the consequences of non-compliance with the GDPR.

• Focus on technology

Technology is essential in enabling organizations to be compliant with the GDPR, but it is only one element of a comprehensive approach to compliance, which includes robust and detailed policies, training, governance processes, and appropriate strategies that cut across not only IT, but also legal, risk management, compliance, senior management, HR and finance.

References

i If the “data breach is likely to result in a high risk to the(ir) rights and freedoms” as noted in Article 33 of the GDPR.

ii http://www.bbc.com/news/business-40441434

iii https://iapp.org/news/a/top-10-operational-impacts-of-the-gdpr-part-8-pseudonymization/

iv https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/data-protection-reform/overview-of-the-gdpr/

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

Subscribe to our free daily newsletter